Circular Economy Blueprints

Design festivals have forever utilised unusual or disused spaces, often those located on the outskirts of town. Economics and scale undoubtedly play their part in this, as does the seemingly ever-expanding number of “design districts” included in such events. But whatever the reason, the use of these ordinarily unseen spaces adds a layer of excitement and intrigue to such festivals, and arguably where you find some of the most interesting and potentially impactful projects and experiments.

Park Royal Industrial Estate in North Acton is certainly a side of London that tourists tend not to visit. Aside from a rather oddly placed but decadently finished Lebanese bakery, it feels like an impenetrable maze of busy and litter-strewn back streets with a continuous stream of delivery vehicles of all sizes servicing the shuttered entrances of everything from garages, wholesale food storage units, AV equipment facilities and in the near future, massive data centres. Aside from Bill Amberg’s studio, on the surface the site doesn’t appear to home too much in the way of the creative industries, but because of the London Design Festival, attention was drawn to a number of art and design studios dotted amongst the more obvious industry taking place in the UK’s largest business estate.

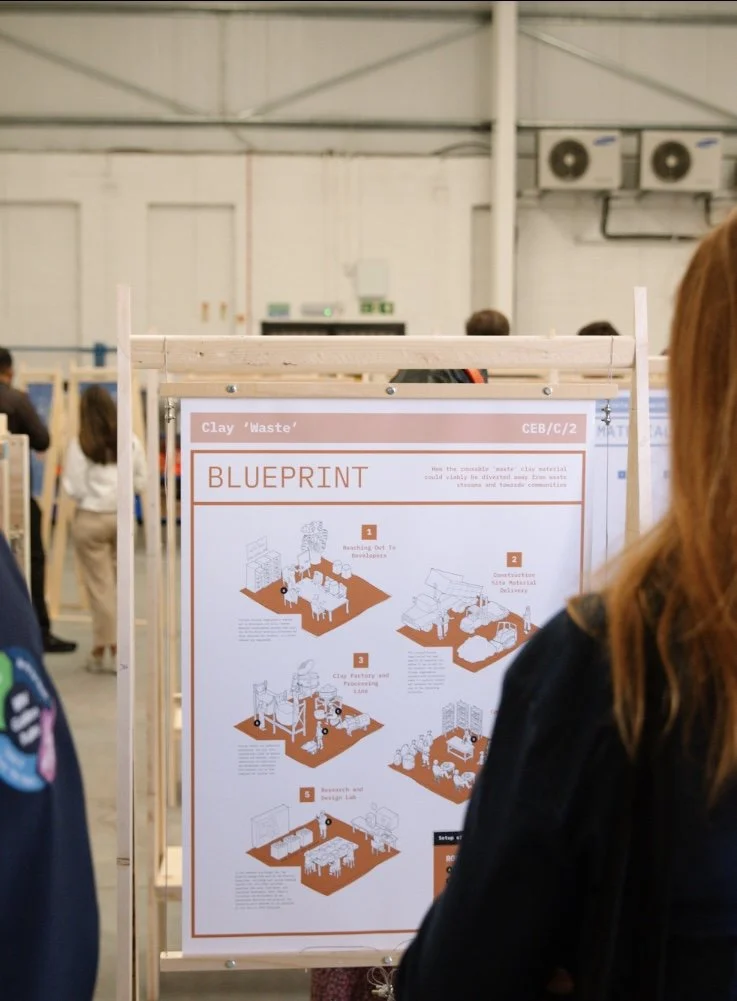

A standout exhibition taking place on the site took place in the newly opened Material Depot on Minerva Road, which showcased the collaborative research initiated by ReCollective and ReMade. Driven by the direct and hopeful question, “How do we seed a bottom-up circular economy in Park Royal that delivers both environmental and social benefits?” the team offered their findings as a series of Circular Economy Blueprints. At a time when the impacts of waste, pollution and habitat destruction as a result of human actions are viscerally on the rise, it seems increasingly apparent that businesses need both plans and action to make a meaningful change. And that’s exactly what the blueprints set out, as the team explains, “Through a series of focussed research sprints, workshops and public exhibitions we have developed each strand into a blueprint for change, setting out the business case and operating model for 5 real-life projects in Park Royal.”

Those projects, which have been sponsored by neighbours Old Oak and Park Royal Development Corporation (OPDC) and HS2, have been developed collaboratively with a panel of industry experts, designers, waste specialists and community practitioners. Each focuses on a specific material that are, until now, seen to be surplus to requirements for one reason or another. For instance, ReMade used the nearby HS2 station development as a case study to explore the salvage potential of timber and other materials used in large-scale concrete formwork. The team identified numerous sheets of shuttering plywood and softwood lengths that can be collected and reused, turning the current model in which only 1% of such timber is reclaimed for future use.

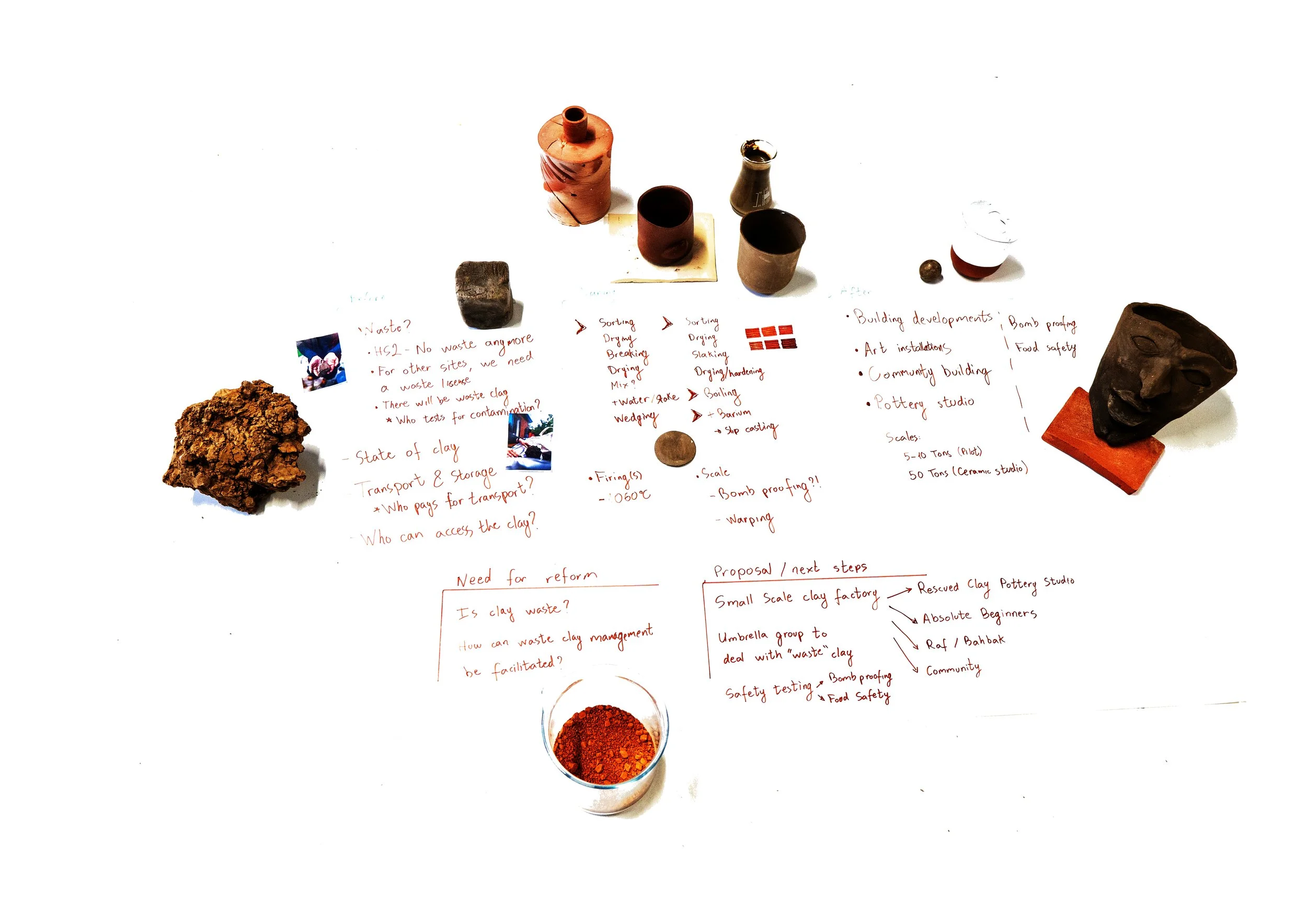

As the studio's name suggests, Rescued Clay were brought in to discover how much clay goes to waste in urban development sites, while experimenting with new systems for positive reapplication of the 14 million tonnes of clay spoil extracted annually from the depths of the UK. Currently it is generally deemed too costly and time-consuming to reprocess spoil, but as with all 5 projects, the team has identified clear steps that businesses can take to make it a profitable process. In this instance, they involve reaching out to developers, organising material delivery to site, a production line and clay factory, a community workshop and studio and a research and design development lab.

Each blueprint also considers costs, roles and even the barriers that might come up along the way. With the case of the Film & TV set building waste project, those barriers include the commonly shared issue of the speed and convenience that existing waste removal systems offer. The ReCollective team ascertained that while film shoots use vast quantities of virgin materials in the form of timber, plastic, paint and windows - amongst other things - very little is reclaimed. Their findings reveal that this is partly due to reliance on subcontractors, which blurs the boundaries of responsibility at the end of the derig, although this forms part of a broader way of thinking in which the industry simply deems it ‘too difficult’ and not cost effective to design in circular systems of production. ReCollective’s research challenges this mindset through a blueprint that ultimately ends with the construction of community buildings.

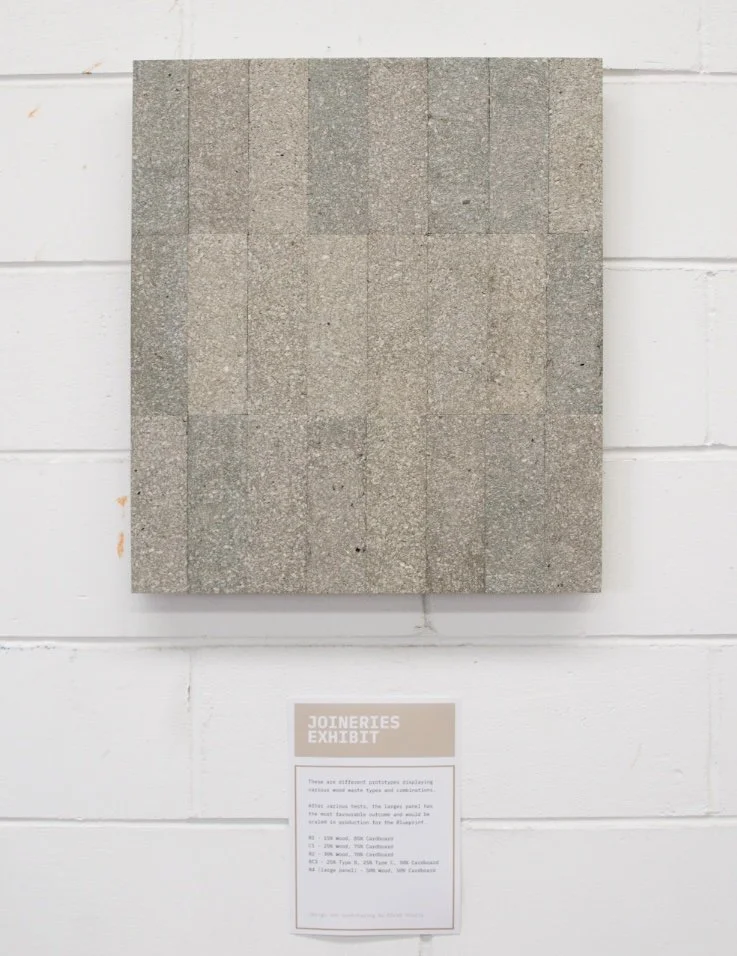

Blast Studio also tackled wood waste, in this case that generated by joineries and furniture makers, culminating their research with a beautiful new composite sheet material composed of wood waste in the form of saw dust and cardboard cups. Extensive experimentation with various material combinations identified the 50/50 mix as the perfect balance of elasticity, rigidity and surface aesthetic. At a time when the cost of timber, notably sheet material, is still affected by the conflict in the Baltic region, along with Brexit, such circular solutions feel timely and highly achievable considering the precedent of materials such as chipboard and OSB, which are already widely used in the industry.

While certain corners of Park Royal look like they’re permanently fixed in the last century, as with all such sites, changes in building regulations and the ever increasing need for redevelopment means that the site will transform in the coming years. The ReCollective team has identified that 5 million sq ft of the site will be demolished and rebuilt in the near future - the Material Depot itself included. As such, demolition waste became another strand of their research and they found that nearly all the material is currently crushed down for reuse as aggregate. While there has been a steady increase in building audits pre-demolition, the ambitious project proposes far more detailed breakdowns and plans for such redevelopments. Using the Minerva Road road site as a case study, the team, led by Alex Toohey, has identified a huge embodied carbon value of the materials at play. The site includes some 333 tonnes of CO2, largely derived from steel, breezeblock and brick. With their blueprint, the team has once again designed systems that culminate in community projects and buildings made from the valuable yet ordinarily damaging waste stream.

The carefully considered and detailed projects represent a hugely positive step in the right direction and one that many more companies can look to get involved with. As the team concludes, the projects, “Will result in the formation of new circular economy organisations and businesses, working towards a reduced number of materials going to waste as well as new affordable materials being made available to the community.”

This article was first published by Design Insider.