Interview with Olivia Aspinall, Do Not Go Gentle

Setting up a design studio that makes interior products for commercial and residential applications is a huge undertaking and one that takes time, various resources, and plenty of energy and innovation, not to mention a bit of luck. So establishing such a brand as one that has a distinct style and offers consistent quality is quite the achievement. Almost 10 years on from its inception, Olivia Aspinall Studio is a practice that would fall firmly in this category, having become synonymous with speckled colourful Jesmonite surfaces. Indeed Olivia was a forerunner in taking up the material in this way, which was spawned by an inquisitive and playful approach fostered while studying Textile Design at Central Saint Martins. Rekindling a collective bygone love of the terrazzo aesthetic through the use of pastel shades and contrasting graphic details, her solid surfaces grew in scale and ambition as her team expanded and evolved. And yet last year, Olivia made the bold decision to close the Nottingham-based studio and turn her attention to material research with a laser focus on sustainable practices. Spending her time between the UK and South America has allowed for time to delve deeply into the field, gaining varied perspectives, as well as gathering invaluable insight into the affects of climate change. By her own admission, this contrast of lived experience has highlighted the rich and progressive design community we have in the UK, especially around the development of innovative materials. Recognising that positive action tends to come with empowerment rather than shame, she has initiated an entirely new studio, Do Not Go Gentle, which aims to assist material specifiers of all kinds in making informed decisions regarding the at-times murky world of sustainability. So why make this bold and brave leap and what expectations does she have for this exciting new venture?

JB: I followed your work with Jesmonite under the Olivia Aspinall Studio banner from the beginning, so was slightly surprised to see you operating under the new name Do Not Go Gentle this year. And when digging a little deeper I realised it’s more than just a name change but an entire pivot into a whole new realm of materiality. Can you tell me a bit about the process and why you made this bold move?

AA: The catalyst for change in my own work was a big combination of frustration and a desire for more knowledge. I was beginning to get frustrated with the way materials were being labelled and promoted, particularly with the material I was working with a lot, Jesmonite. It was a material I formed a real love-hate relationship with as it is an amazing material to work with, so versatile and adaptable, however the marketing of it as an ‘eco’ material was difficult for me. Yes, it is a water based resin, so much more friendly to humans and the environment than traditional epoxy casting resins, however that isn’t the full story. For example the companies policy around taking back the really strong plastic packaging the material was supplied in was very weak and not circular, or when you start looking at all the components of the material you definitely cannot throw them all into the category as ‘eco.’ So it was this loose labelling that frustrated me and got me questioning what I was doing. And I am not saying here that Jesmonite is good or bad, it’s a great material for so many contexts, however it was the way the material was being talked about that made me frustrated. I then started working with the amazing Katie Treggiden on her Making Design Circular Masterclass, which threw up so many more questions and also ignited my desire for more knowledge on the subject.

Cutting a long story short, after months of trying to change my studio from the inside, I decided to take a different tack. I started educating myself further around sustainability within business and took a really intense course at Cambridge which was all about leading and driving change through the challenges and opportunities brought up by the current climate emergency. After this Do Not Go Gentle started to develop and I started to try and work out the best way I could use my passion in this area to form a business and help share knowledge.

JB: Research is so important when it comes to ascertaining whether a material has genuine eco credentials, so I can only assume that you’re doing a lot of it. How are you going about this, are there others involved, not least manufacturers themselves?

AA: There is a huge collaborative approach to my research. I feel like currently there is a big disconnect between material manufacturers and the architects or designers specifying the materials. I want to try and bridge that gap, through knowledge sharing and collaboration. One challenge we have at the moment is that architects for example want to make sure they are specifying low impact or sustainable materials and will often be asking for lots of accreditations and figures from a material supplier, but the problem is that these aren’t all standardised. By speaking to material producers the impression I am getting is that they feel overwhelmed by which accreditations to strive for, whether it be making sure they have an ISO14001, or Bcorp registered products, for example. So I am trying to understand the challenges faced by the material producers as well as the needs faced by those wanting to specify. At the moment as I collect more information, I am really relying on suppliers who want to share as much information as possible with me.

I am approaching as many suppliers as are willing to talk to me, with a focus on the UK and Europe to start with. In general I have found the response really productive, and quite mixed. There are a number of amazing producers that are ticking all the boxes around circularity as well as how they put their message across, however there are also those that are doing great things, but don’t necessarily have the marketing or language around sustainability as clear. It’s interesting to talk to these manufacturers to try and understand their materials and the challenges they face. I really try my best to talk to all manufacturers with an open mind; I don’t just want to talk to those that have all the boxes ticked already.

JB: So how do you then discern any sense of rating for the materials you are researching?

AA: When looking at materials it isn’t a black or white situation around whether a material is ‘good’ or ‘bad.’ It all depends on context. I have developed my own parameters to try and assess materials and have categorised these under 9 headings which I call my Good Design Codes; circular, transparent, human kind, local, hand crafted, innovative tech, bio based, managed resources and collaboration. Within these categorises I also look into figures for CO2e, water usage and energy usage. Working this way helps specifiers decide what is most important to them, their project and the context within which they are working.

I am translating the information I gather in a number of ways. The big aim is to build a materials database that has all the crucial information but still allows creatives, designers and brands to make decisions in an efficient way. I want to take a layered approach to information. This subject is so complex, with so many factors at play that I don’t think it’s right to dumb down information, however layering information so that people can be confident they are making a low impact choice initially, but then dig into the figures if they need to. That’s the aim.

JB: Are you finding that there is genuine drive to make change from those who are in most need of doing so, or at least those who are engaging with you?

AA: This is complicated. When we are talking about the design industry and materials we are also need to be talking about construction, as this is the industry that really uses lots of resources. Then the big materials within this area are things like concrete and steel. Concrete is the most commonly used man-made material globally, and due to its cement content creates a huge amount of emissions. C02 is produced when the limestone is heated to very high temperatures to produce clinker. The push in this area is with carbon capture, so injecting carbon into the concrete as it’s being produced to be able to trap the carbon in the concrete. There are lots of companies currently racing to perfect this technology, as ultimately there will be lots of money to be made from a good solution. There are some critics of this type of technology, as it has historically been linked to oil companies using the eco branding of ‘carbon capture’ to perform what was in reality enhanced oil recovery. I would also be very wary of anything using carbon capture to brand its production as carbon negative. So these big industries are making strides forwards but we need to keep our eyes on the reality of what is happening and not take all good news on face value.

On a more positive note there are so many amazing designers as well as manufacturers wanting to make positive change and working really really hard to do so. Lots of people doing their bit will make a big difference.

For example, Smile Plastics are well known producer of recycled plastics within the UK now. I always like to shout about them as they are really taking on the challenge of scaling up production with their facilities based just outside of Swansea. There are also companies like Margent Farm in Cambridgeshire who have collaborated with Cambridge Univeristy to produce really gorgeous hemp composite panels. Both of these materials have been around for a while but they are examples of UK producers making strides in different areas of surface production.

JB: In your experience, how prevalent, and with it, how damaging is green washing?

AA: When I talk about greenwashing I always start with a comparison to the fashion industry, because it is something most people have some knowledge of and can use as a benchmark. I don’t feel like any materials companies I have come across are deliberately greenwashing like we have seen in the world of fashion. We know the fast fashion industry is driven by people buying more all the time, companies like H&M offer recycling schemes as a solution, when in reality the global systems for recycling textiles are not developed enough to deal with the volume of clothing that is produced or the types of mixed textiles most cheap garments are made of. Chemical recycling technology is developing, but it’s not there yet. I say this because these fashion companies are always going to be greenwashing in some way, because they are never telling the full story.

What I think is happening in design at the moment is that some companies panic about their position or their processes and start to use buzz words in a really vague way. I don’t think this is as intentionally deceptive as we see in fashion however it is the vagueness of words such as ‘compostable’ or ‘sustainable’ that can be a problem. Take the phrase compostable as an example; lots of food packaging or plates and cutlery used for takeaway food are labelled as compostable. However, most of these items are only compostable in commercial composting facilities that can create the right conditions, and if that fork or plate or piece of compostable material ends up in landfill instead, which is highly likely, we end up doing more harm than good as these items in landfill will release methane. So, this is an example of what could be a good solution actually not being great because of the lack of infrastructure there to support the material innovation.

On the positive side, there are companies out there that recognise this problem and are being a lot more specific on their messaging. NOTPLA is a really amazing UK based company creating packaging and paper from seaweed and other plants. They are very specific to describe their materials as ‘home compostable.’ This way customers know exactly how to compost the material. With phrases like biodegradable I would always recommend people to ask under what time frames is this material biodegradable. You always need to try and dig a bit deeper into these terms.

JB: How are you turning this hard and no doubt difficult and perhaps saddening work and insight into a business? How have you shifted from a commercial brand to one that seeks to offer knowledge and information?

AA: I think that although work in this field can seem daunting and often overwhelming, I ultimately like to frame it as an opportunity for business. I feel like we are in the situation we are in now in terms of everything the world is facing environmentally and we can either shy away from it or face it head on. This mentality is where the name of the new company came from, Do Not Go Gentle. I want to help companies, designers and creatives stride forward confidently. We might not get everything right first time, but with resilience, creativity and determination amazing materials, products and companies will shine through.

Shifting from a person that makes products to a person that seeks to offer knowledge and information has been a challenge and something I am still navigating. I am currently letting my deep interest in the area drive this. I get way too excited learning about manufacturing methods and new innovations

that I hope this shines through. There is also demand within the design industry for this knowledge, it’s a complex subject and sustainability work also seems to carry with it a lot of heavy emotions. I want to show that creating more sustainable and low impact businesses isn’t only about doing the morally ‘right’ thing; it’s about creating businesses that will thrive into the future.

JB: You mentioned a few companies earlier, but are there any specific materials you discovered that are truly radical and/or useful in turning the tide?

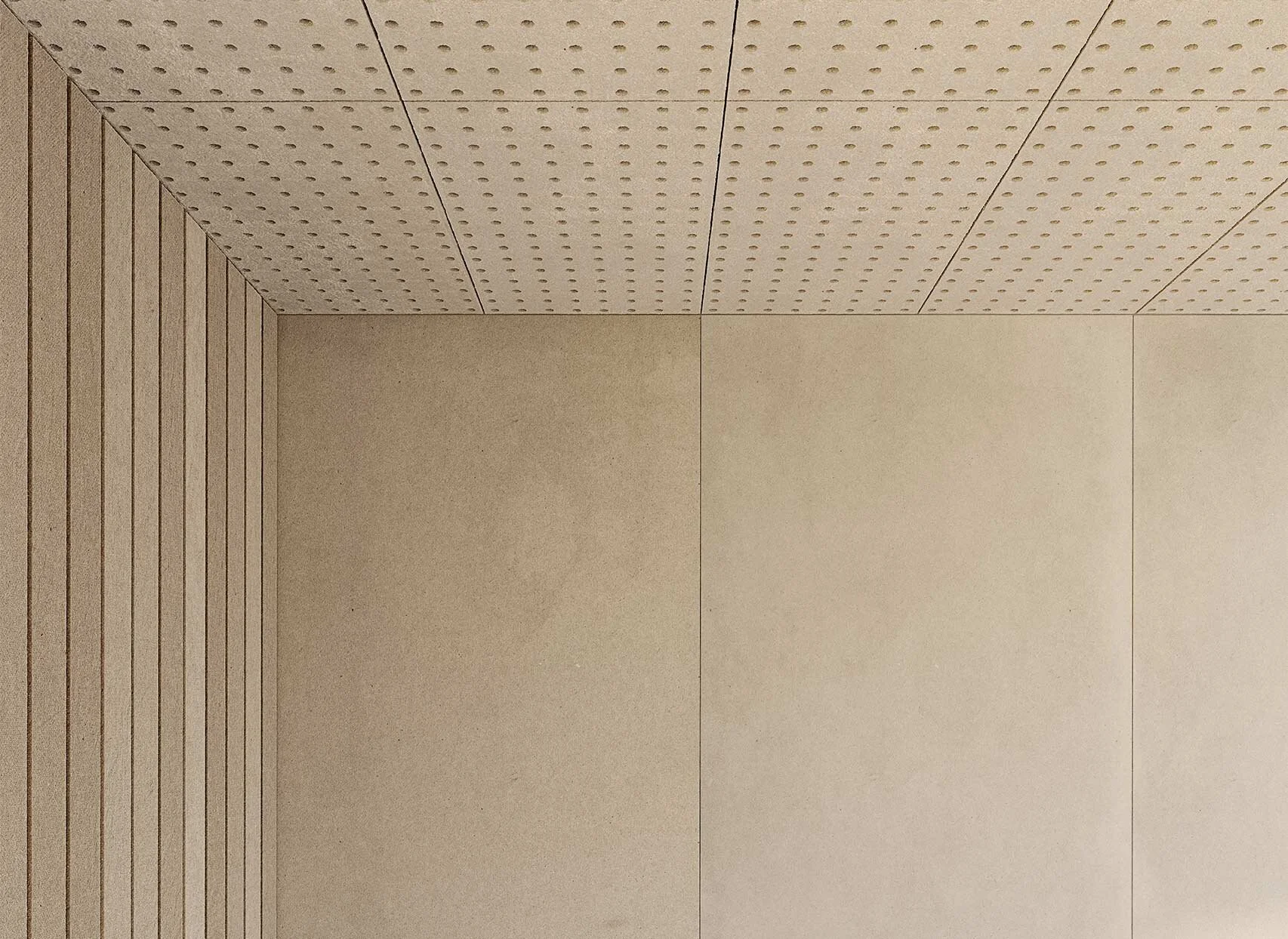

AA: With material innovation and development, I think the biggest challenge is scale. We need these innovative materials to be produced at a scale so that they can replace their higher impact alternatives. In the UK and Europe especially, we have some many exciting designers creating exciting materials but the challenge is scaling them up and also getting industry used to working with new materials. I love to talk about Honext, a cellulose based sheet material produced in Spain from the by-products of the paper milling industry. They have lots of amazing credentials, they are circular; their production facilities are on the same site as where their raw materials are being collected from, massively reducing their emission from transport. However, what I find most interesting is they are the first cellulose sheet material, or even alternative low impact material to be stocked at a sheet supplier in the UK. So, you can buy Honext from James Latham, where you would usually be able to source plywood or MDF. This makes these sorts of materials so much more accessible.

JB: And how can individuals and/or brands work with you? What can they expect from the relationship?

AA: Individuals or brands can work with me in a number of ways currently, and this will develop as DNGG grows. For individuals that want to start expanding their knowledge in the area, they can join my insight sessions and subscribe to the materials database once it is launched, currently you can join the waiting list for this. I also work with individuals or brands as a consultant whether that be researching and delivering material options for an individual project, helping to keep their teams knowledge up to date in the area or helping them educate and excite their clients around sustainable materials or circular design practices.

This article was first published on Design Insider