The Power of Water

In a year of damning indictments about the UK’s water suppliers, it feels like water, as a resource is more important than ever. What seems like ever-increasing reports of companies being rumbled for allowing wastewater to enter fresh sources in and around the British Isles have become an unsettling norm. Recent responses from the companies in question only serve to make this dysfunctional status quo all the more galling, with suggestions that the costs to fix the sewage system will be passed directly onto customers in the future. Ironically, as the rain begins to pour, the problem will only get worse as providers have regularly cited that the system can’t handle such spikes in abundant fresh water, leading to mass overflows of dirty water into our seas and rivers.

Coleridge’s renowned expression “Water, water everywhere nor any drop to drink” sadly rings true, for whilst we may still be able to heedlessly turn on a tap and drink clean water here in the UK, the effects of these spillages negatively impact the ecosystems of these waterways. Not to mention causing serious risk to any wild swimmers brave enough to delve into the murky, and potentially freezing, waters. What’s more, human activity across the globe has led to a huge reduction in the natural water cycle, with the flow being directed away from soil and into drainage, which in turn increases the chances of drought and flooding.

Water is an elemental lifeblood for all living things and given this universal need, is something that designers have consistently turned their attention to. This was apparent during two international design and architecture events this year - Dutch Design Week and the Venice Architecture Biennale.

Numerous water-based projects were spotted in Eindhoven and indeed the importance of the topic was underlined by the work of the Embassy of Water (aside from the very fact that such an organisation exists). The Netherlands is said to have the worst water quality in Europe, which the Embassy has described as a “water crisis.” Their aim is to help restore the water cycle and encourage the rather poetic notion of listening to the Voice of Water. In fact, there were literal listening ears positioned over the Dommel Canal, inviting the public to take in the sounds of the moving current.

Over in the large greenhouse-style pavilion, the team brought together a series of design proposals that seek to offer solutions that “borrow, reuse and restore” rather than continuing with the current, long-standing system of “extract, use and discharge.” The space, designed by Studio Corvers, was itself part of the water cycle, which the Embassy’s Creative lead Anouk van der Poll said shows that “buildings can function as a collective, natural purification system, where we borrow water from the cycle and return it to nature in cleaner and more vital way.” An emphasis is placed on changing attitudes and showing that “things can already be done differently,” something that architectural practice Mulderendevries have highlighted with visualisations that bring together the Embassy’s insights generated during their 5 years of existence. They depict a “virtual future of regenerative water design in our residential and living environment,” whereby decentralised purification systems work in harmony with the natural water cycle, becoming part of the ecosystem rather than imposing themselves upon it.

Another installation found over at Dutch Invertuals drew attention to the cycle and flow of water, albeit with a rather more playful approach. Flow is a water fountain-cum-marble run, with a perilous ending for the beads of water akin to the board game Mousetrap. Utilising gravity, water is released from atop a stilted structure made up of various sections of felt and textile-covered forms. Each has its own characteristics and shape, with channels funneling the water down the swooping, staggered ramps, until they finally drop off their last edge…onto an ever-on hot plate.

The perpetual cyclical experience is the brainchild of designers Béla Bezold, Studio Edhv, Ralf Gloudemans and Teresa Fernández-Pello, who describe how the elemental properties of water serve as a reminder to connect with the real, rather than digital, world:

“In our technology-infused society, every aspect of our life is being altered. We hardly even notice how far we have drifted off from our physical habitat and the things that are truly important. We have shifted towards a flow of data and information, disconnecting us from the valuable experiences that make life beautiful.

Can we re-establish a deep connection to our physical reality by creating beautiful experiences?”

The symbolic power of water was also explored by recent graduate of the Design Academy Eindhoven, Marta Moskova. This year the must-see graduate show took up residence in a currently vacant shopping precinct in the centre of town, and on entering, visitors were welcomed by the gentle trickle of water over a large boulder. Welcoming a drink from the carefully positioned pool at the heart of the piece, Fountainhead prompts thoughts regarding our almost ritualistic relationship to water, while subtly juxtaposing flow and solidity along with hard and soft. The sizeable work is in fact sculpted from copper sheets, meaning the water itself is in a continuous state of purification, although the metal was indeed formed around the surface of actual rock formations found in Bulgaria.

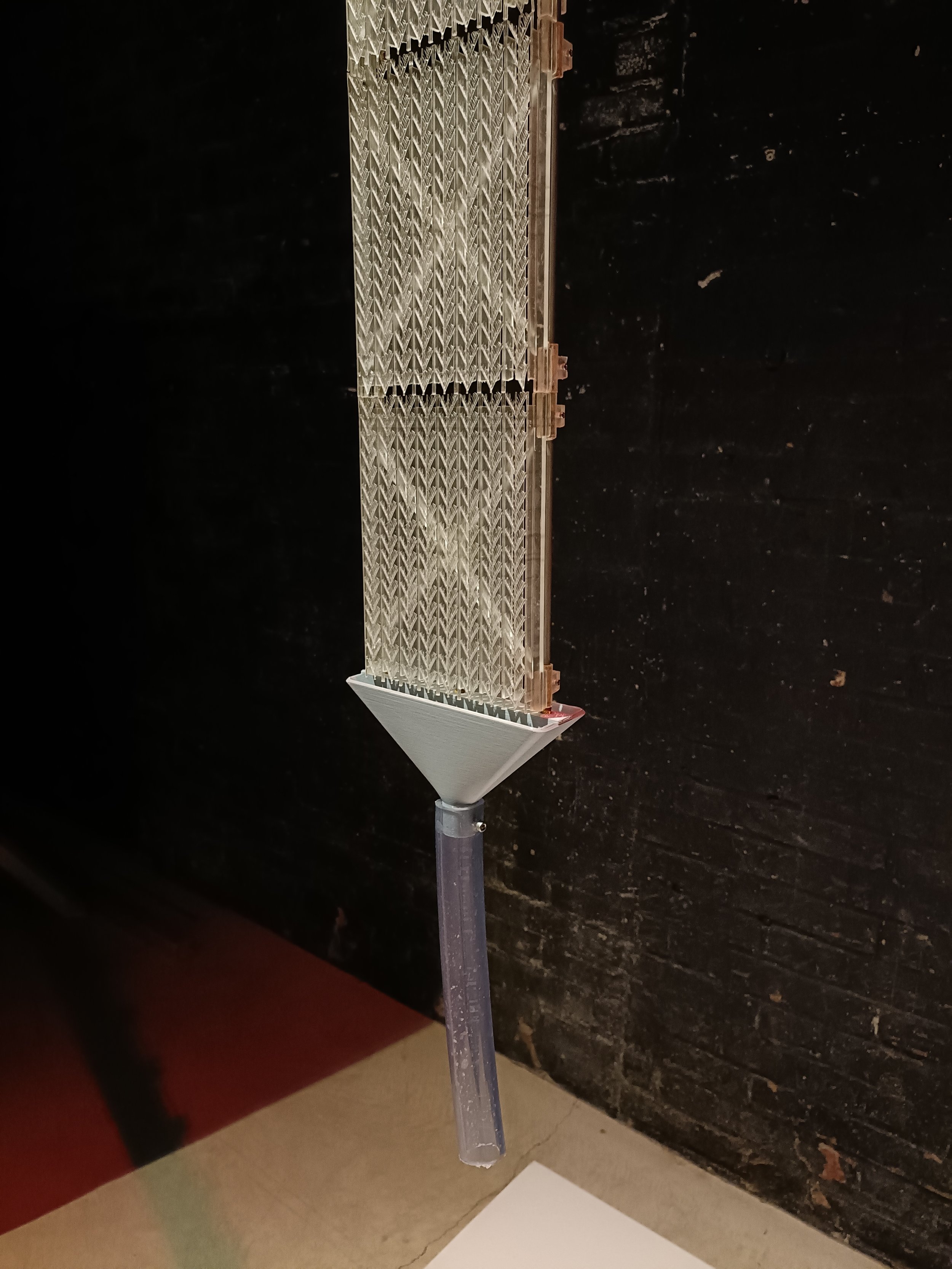

Rather than focusing on flow, Nebula, by fellow DAE graduate Kyran Knauf, is concerned with capturing water. Given that in many places of the world there is already a scarcity of clean water - and with many more set to follow - the retention system feels timely. While the 3D-printed mesh modules may aesthetically reflect the technological underpinnings of the project, there is biomimicry at play here, with inspiration taken from the Cottula Fallax plant. Like the leaves of the plant, the fine hair-like nodules on the surface of the vertical panels capture the water found in mist and channel it downwards where it is funneled and collected ready for cleaning and redistribution. Although the innovative system is still being developed, not least in terms of finding more sustainable processes to create the units, it shows much promise.

As the Venice Architecture Biennale draws to an end it’s worth noting that a number of the international pavilions drew at least some attention to the state of water or sanitation in their country, although the efforts of Greece and the Netherlands did so with some urgency. Costis Paniyiris and Andreas Nikolovgenis, curators of the Greece pavilion, did so explicitly with Bodies of Water, which focused on the Hellenic territory, where human intervention has long geophysically shaped the landscape.

The impact has largely been negative, with overgrazing and anthropogenic interventions starting as far back as the tenth century resulting in devastating desertification. The project addresses all sides of the impact of the resulting introduction of reservoirs in the region, as the team explains:

“After the establishment of the modern Greek state, and with great intensity after 1950, water reservoirs as well as drainage, irrigation, water supply, and hydroelectric projects constitute a support system for agricultural production and all kinds of human activity. It is a transformation of the land where a new hydro-geological map of the country is invented, constructed, and operationalised.”

As discussed, although still rather shockingly, the Netherlands is currently judged to have the lowest quality water in Europe, so it’s no surprise that Plumbing the System looks to challenge the current state of affairs in the country. Once again, the emphasis is placed on rethinking existing extractive and exploitative principles, with architecture at the heart of reimaging a more just and ecologically resilient future. Water is, at least in part, used as a metaphor, with Carlijn Kingma’s large-scale drawing titled The Waterworks of Money acting as an initial springboard into the complexity of the financial and regulatory systems at play in the country (and similarly elsewhere). In a more literal sense, the pavilion also serves to highlight other practical means of dealing with water itself, with a water retention system installed within the space, and documentation of how it works readily available for all to consume.

This endeavour, along with the work of the Embassy of Water, and all the projects mentioned, underlines the need for collective, collaborative change in the quest for cleaner, fairer and more sustainable water for all. The proof is in the pudding, with Holland’s Minister of Infrastructure and Water Management Mark Harners quoted as saying that he and his government are “listening” to water. Perhaps it’s high time the UK government did the same.

This article was originally published by Design Insider