Robots That Build, with Humans

Robots and AI don’t always get the best rap, not least in the world of cinema. From the sentient HAL 9000 computer to the misunderstood Robby the Robot, and right through to the destructive force of the Terminator, we have often imaginatively shown them in a negative light.

Yet, their usage in the world of architecture is ever-increasing, so much so in fact that professors at the Eindhoven University of Technology are intent on challenging the now well-established paradigm of optimisation and efficiency in robotic fabrication in architecture. Their exhibition titled Robots that Build: The Extensions of Man, explored how such advanced fabrication techniques are also combining with and helping to extend traditional craft manufacturing techniques.

As co-curator, Cristina Nan explains, “By focusing on the hybridized workflows of human-machine processes required by robotic fabrication, the exhibition explores how the redefinition of both craftsmanship and the master builder within architecture is leading to new ways of building and, eventually, of living.” The case that working with robots alone to manufacture might be efficient but cold is countered by the idea of bringing in the all-essential human touch and with it, a culture that adds more relatable dimensions to the outcomes. As fellow curator Sergio M. Figueiredo elucidates, “Effectively, within the context of robotic fabrication, skilled work by craftsmen is crucial to ensure an intelligent—and thus meaningful—translation of craft from human to machine, specifically with the robot acting as the craftsman’s extension. This much is made explicit throughout the exhibition, as the craftsman’s hand (often hidden in robotic fabrication) is not just revealed, but also celebrated.”

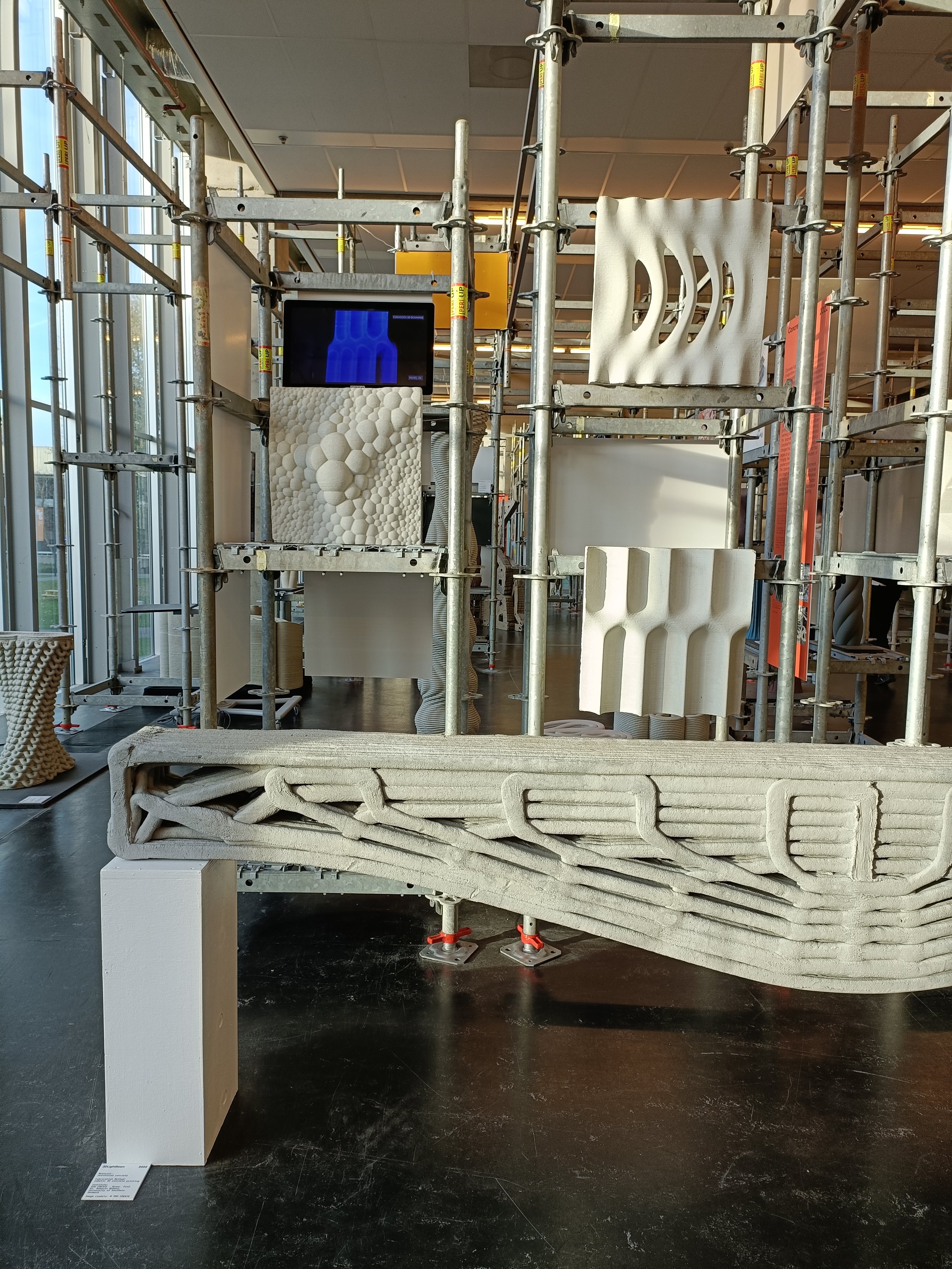

The exhibition did indeed showcase an array of different processes and material innovations via 3D prototypes, imagery and written information. Whilst one might expect to see a range of examples of additive manufacturing, which of course there were, visitors were also invited to discover new ways of robotic weaving, compacting dirt and stacking bricks via collaborations between humans and robots. Materials themselves play an integral role and as such prior knowledge of their properties is essential along with early involvement of the human hand in experimenting with their possibilities. Our input and decision-making abilities are integral in the 3D printing of a bridge or the reaction of mouldings for the Sagrada Familia, regardless of whether the making process is carried out by digitised and automated processes alone. As Figueiredo elaborates upon once again, “As it brings together the work of advanced and innovative research groups exploring the boundaries of robotic-craft fabrication, Robots that Build questions issues of cultural specificity, cultural significance, and socio-cultural relevance of robotic fabrication in architecture, design and construction, effectively examining the current state of robotic fabrication and what is conventionally understood as craft.” This is further highlighted by the volume of research groups involved, including TU Eindhoven, TU Delft, ETH Zurich, Hong Kong University, Institute of Advanced Architecture of Catalonia, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, and Newcastle University to name a few.

The work on display very much suggests that 3D Printing promises to revolutionize the way we design and build our cities. Working at such a large scale requires malleable materials that are up to the job of constructing seamless and durable structures. The 3DPA research program at IAAC explores how clay and earth-based materials, which were commonly used as construction materials before the start of the Industrial Revolution, might come into effect. Working closely with 3D specialists such as Italian brand WASP, they propose a synergy of digital design and fabrication in their approach to making, which could produce a wide variety of building styles that can adapt to the local context, that is climatic, cultural, and economic. Their 3D printing explores complex geometries with an emphasis on the application of façade systems that are both visually arresting and functional. And as the organisers are keen to point out, unlike most of the most commonly used building materials today - concrete, steel, and glass - clay and derived earth-based material systems demonstrate a significantly reduced CO2 footprint and a higher potential for reuse and recycling.

3D clay printing is also the focus for Studio RAP with their project that looks to leap off from where ceramic artisans have long-established a signature style of blue and white glazing in the historic Dutch city of Delft. As they explain, “By fusing 3D clay printing, computational design, and artisanal glazing, New Delft Blue attempts to unfold a new architectural potential of ceramic ornamentation of the 21st century.” Working with an algorithmic approach to 3D pattern design along with manufacturing constraints such as maximum overhang, shrinkage and internal support structures, they have produced nearly 3000 tiles with an array of geometric dimensions. These variations in the seemingly organic forms allows for greater play with the intensity of the deep blue glazing, which further adds to the unique aesthetic.

Whilst the cement industry may be one of the main producers of carbon dioxide that enters the atmosphere, 3DLightBeam deploys computational design and robotic 3D Concrete Printing (3DCP) to help reduce concrete CO2 emissions. As the team at SDU CREATE are keen to underline, “3DCP enables multi-hierarchical stress-based design optimization. 3DLightBeam is shape-optimized to maximize bending capacity while reducing weight.” The internal infill design is actually inspired by the formation of bones, one of nature's most efficient and effective building structures.

Other work on display also looks to further challenge the impact and provenance of the raw materials used within construction, which is arguably most ecologically sound when employing bio-based substances. One such example is the BioPolymer Wall, which demonstrates how cellulose-based biopolymer can be used to 3D print on a large scale. Whilst that sound like an obvious avenue of exploration the research team at the Centre for Information Technology and Architecture are keen to point out that “Although cellulose is the most abundant organic compound on Earth, biopolymers are unruly materials as they are less stable and less durable than their petrochemical equivalents.” At this fledgling stage of development, the team acknowledges that structures made from these substances may have to operate with shorter life spans, novel aesthetics and more varied uses than their counterparts - but that this need not be a bad thing. They instead choose to see their uniquely layered wall as a celebration that, ”combines geometric design aspects and parametric workflows with fabrication and material system constraints to bring an unruly material into architectural tolerance through a new digital tectonic expression specific to digitally designed, robotically produced biopolymer prints.”

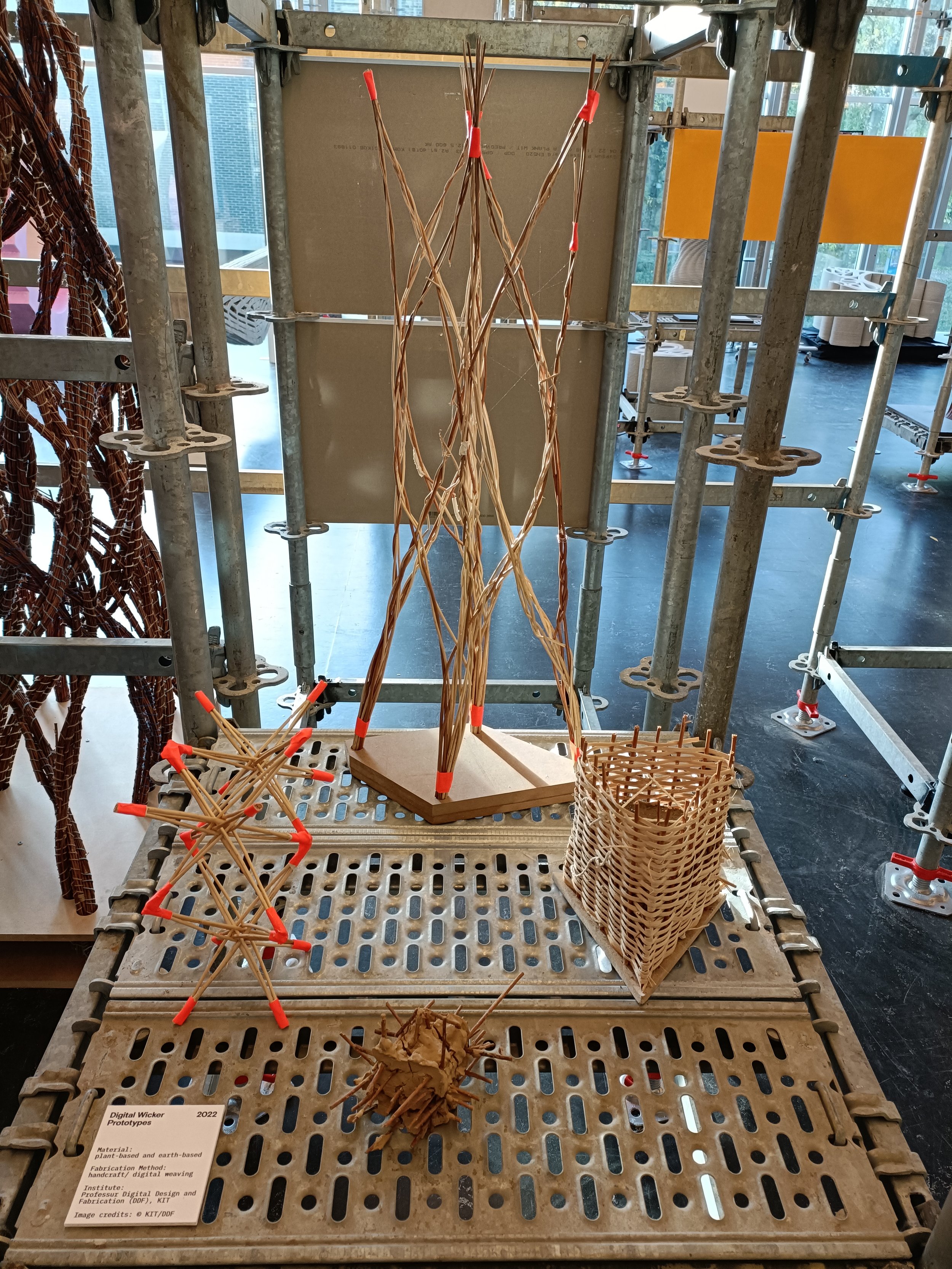

Elsewhere on display were experiments with more traditional hand-making processes, notably wicker weaving, a technique where long thin sticks, stems or reeds are woven together to make baskets and structural boundaries. The team behind these experiments are driven by a desire to look back to local, renewable materials and techniques but also recognise the extended potential that using digital design and fabrication can offer the world of architecture. Combining hand and robotic weaving of willow, reed and hazelnut along with straw, seaweed and earth allow for structurally and ecologically sound forms that are made even more efficiently than ever before. As the team suggests these, “methods can re-enable the industrialization of natural materials through the accommodation of deviations and abnormalities, which currently represent one of the biggest obstacles in standardized serial production systems.”

So whether it’s bridges, buildings, walls, columns or decorative surfaces, it seems we’ll been working even more closely, and positively, with robots than the world of Sci-fi has ever imagined.

This article was originally published by Design Insider